Joins: Unleashing The Power Of SQL

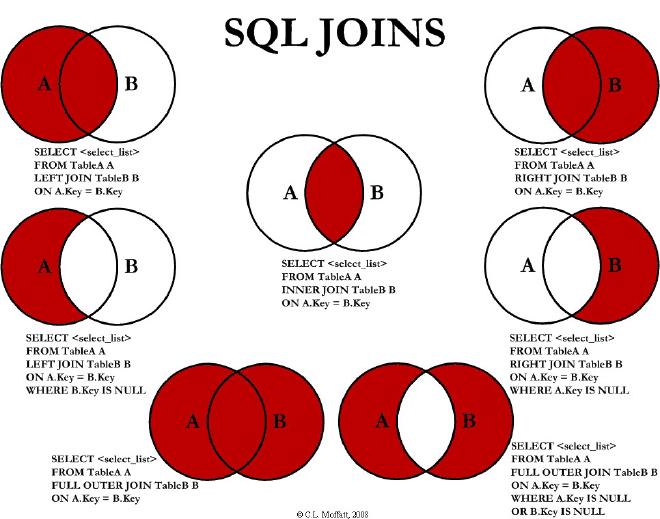

One of the most powerful tools in a SQL coder’s arsenal is the JOIN command. Technically speaking, it allows the user to combine tables linked by a primary key and perform queries on a new table defined by the user’s given criteria. More broadly, JOINs are what make relational databases work, allowing specific information to be stored in different tables and combined later through relationships between specific columns in each table. There are essentially 6 types of JOINs in SQL:

- Inner Join: The shorthand for this type of join is simply JOIN. It returns the rows present in both the left and right table only if there is a match.

- Full Outer Join: The shorthand for this type of join is Full Join. It returns all the rows present in both the left and right tables, regardless of a match.

- Left Outer join: The shorthand for this type of join is Left Join. It returns all the rows present in the left table and all matching rows from the right table (if present).

- Right Outer Join: The shorthand for this type of join is Right Join. It returns matching rows from the left table (if present) and all the rows present in the right table.

- Self Join: This command is used to join the table with itself. This can be used to calculate a running total of a value, among other uses.

- Cross Join: This is used to return the Cartesian product of two tables. The number of rows returned equals the product of the number of rows from the left table and the number of rows from the right table. (i.e. A table with 5 rows cross joined with a table with 7 rows returns 35 rows.)

INNER JOINs are the most common type of SQL JOINs. Below is the basic structure of an inner join query:

SELECT column1, column2, …

FROM table

INNER JOIN another_table

ON table.id = another_table.id

WHERE condition(s)

ORDER BY column, … ASC/DESC

LIMIT num_limit OFFSET num_offset;

Let’s break down the other components of this generalized query for those new to SQL:

- SELECT specifies which columns are pulled from the first table.

- FROM points to the table from which the columns are pulled.

- WHERE specifies certain conditions for which matched data is pulled. (WHERE column1 > 50)

- ORDER BY specifies which column

- ASC/DESC determines whether the values will display in ascending or descending order.

- LIMIT specifies the maximum number of rows returned (LIMIT 100 returns the first 100 rows).

- OFFSET sets the number of initial values to skip. (OFFSET 10 will show values in rows 11+)

INNER JOINs: The Most Useful of JOINs #

Now that the basics are covered, let’s take a look at the inner join and see how it functions:

JOIN another_table

ON mytable.id = another_table.id

Why is the keyword INNER ommited from this example? As INNER JOIN is the default JOIN in SQL, simply using the JOIN command will perform the same function as INNER JOIN.

On the first line of this code snippit, the user specifies the second table (another_table) that will be JOINed with the first table (table). Since INNER JOINs return matching rows, the matching criteria must be specified. Here the user uses the “id” column as the primary key for both tables. The resulting table will display any combined rows where the “id” value matches in both tables.

OUTER JOINs: Including Unmatched Rows #

In some situations, in addition to returning matching rows between two tables, you want to include all unmatched rows from one or more tables as well. That’s where OUTER JOINs come in.

FULL OUTER JOIN #

FULL OUTER JOIN returns the set of all records from both tables. If there is a match, the rows will be returned similarly to an INNER JOIN. If there is no match, a row will be returned with null values for the other table. For example, take the following two tables:

| First | Last | First | Last | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Doe | Beth | Doe | |

| Mary | Smith | John | Smith | |

| John | Kate | Mary | Ruso | |

| Mary | Dorn | Dan | Donahue |

If we perform a FULL OUTER JOIN between these two tables:

SELECT * FROM Table1

FULL OUTER JOIN Table2

ON Table1.last = Table2.last

The result is the following:

| First | Last | First | Last | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Doe | Beth | Doe | |

| Mary | Smith | John | Smith | |

| John | Kate | (null) | (null) | |

| Mary | Dorn | (null) | (null) | |

| (null) | (null) | Mary | Ruso | |

| (null) | (null) | Dan | Donahue |

Notice the null values where no match was detected.

NOTE: MySQL does not allow for the FULL OUTER JOIN command, but it can be emulated:

SELECT * FROM Table1 LEFT JOIN Table2 ON Table1.last = Table2.last UNION SELECT * FROM Table1 RIGHT JOIN Table2 ON Table1.last = Table2.last

LEFT and RIGHT OUTER JOINs: Introducing Null Values in Query Results #

LEFT and RIGHT OUTER JOINs function similarly to FULL OUTER JOINs, but instead of returning unmatched rows from both tables, it only returns either unmatched rows from the first or the second table. A LEFT OUTER JOIN will return unmatched rows from the 1st table, while a RIGHT OUTER JOIN returns those from the 2nd.

For example, if you were to do a LEFT OUTER JOIN on the above tables:

SELECT \* FROM Table1

LEFT OUTER JOIN Table2

ON Table1.last = Table2.last

The result would be:

| First | Last | First | Last | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Doe | Beth | Doe | |

| Mary | Smith | John | Smith | |

| John | Kate | (null) | (null) | |

| Mary | Dorn | (null) | (null) |

And with a RIGHT OUTER JOIN, the syntax is nearly identical:

SELECT \* FROM Table1

RIGHT OUTER JOIN Table2

ON Table1.last = Table2.last

This is the result:

| First | Last | First | Last | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Doe | Beth | Doe | |

| Mary | Smith | John | Smith | |

| (null) | (null) | Mary | Ruso | |

| (null) | (null) | Dan | Donahue |

Notice that the null values are in the 2nd table with a LEFT OUTER JOIN, while the null values are in the 1st table with a RIGHT OUTER JOIN.

SELF JOINs #

A SELF JOIN is, as the name implies, a SQL query where a table is joined with itself. It’s used to compare values in a particular column with other values in that same table. A practical use of this is to create a running total of integer values. Below is an entirely impractical example that simply returns all first names in the table, as the same variable is being compared. In order to do this, we have to create two ailiases both linked to the same table and join them together:

SELECT a.first, b.first

FROM table2 a, table2 b

WHERE a.first = b.first;

Here’s the result:

| First | First |

|---|---|

| Beth | Beth |

| John | John |

| Mary | Mary |

| Dan | Dan |

Again, this isn’t particularly useful, but it’s a proof of concept without comparing integer values.

CROSS JOINs: All Your Rows Are Belong to Us #

The final and rarely used join is the CROSS JOIN. It returns the cartesian product of the two tables. This joins “everything to everything”, meaning a table with 4 rows CROSS JOINed to a table with 5 rows returns 4*5 = 20 rows.

For example consider the following code:

SELECT \* FROM Table1

CROSS JOIN Table2

A table with 4 rows CROSS JOINed to a table with 4 rows returns 4*4 = 16 rows:

| First | Last | First | Last | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Doe | Beth | Doe | |

| Mary | Smith | Beth | Doe | |

| John | Kate | Beth | Doe | |

| Mary | Dorn | Beth | Doe | |

| John | Doe | John | Smith | |

| Mary | Smith | John | Smith | |

| John | Kate | John | Smith | |

| Mary | Dorn | John | Smith | |

| John | Doe | Mary | Ruso | |

| Mary | Smith | Mary | Ruso | |

| John | Kate | Mary | Ruso | |

| Mary | Dorn | Mary | Ruso | |

| John | Doe | Dan | Donahue | |

| Mary | Smith | Dan | Donahue | |

| John | Kate | Dan | Donahue | |

| Mary | Dorn | Dan | Donahue |

Since there are no conditions used in this code, it isn’t particularly useful. But if you need to look at all the possible permutations of row combinations, it can be helpful.

Extra Credit: Why are my commands in all caps? #

Technically, SQL is not a case sensitive language, so capitalizing command isn’t required. It does, however, make the code much more readable. If there’s any possibility that someone else will eventually modify the code, best practices suggest making the SQL commands all caps so that another person can easily identify them. It’s just common courtesy, and the sooner you can get in the habit of doing so, the better. Your peers will thank you for it.

So there are the 6 main JOINs used in SQL, from the incredibly useful INNER JOIN to the occasionally useful CROSS JOIN.